Developing a derivative

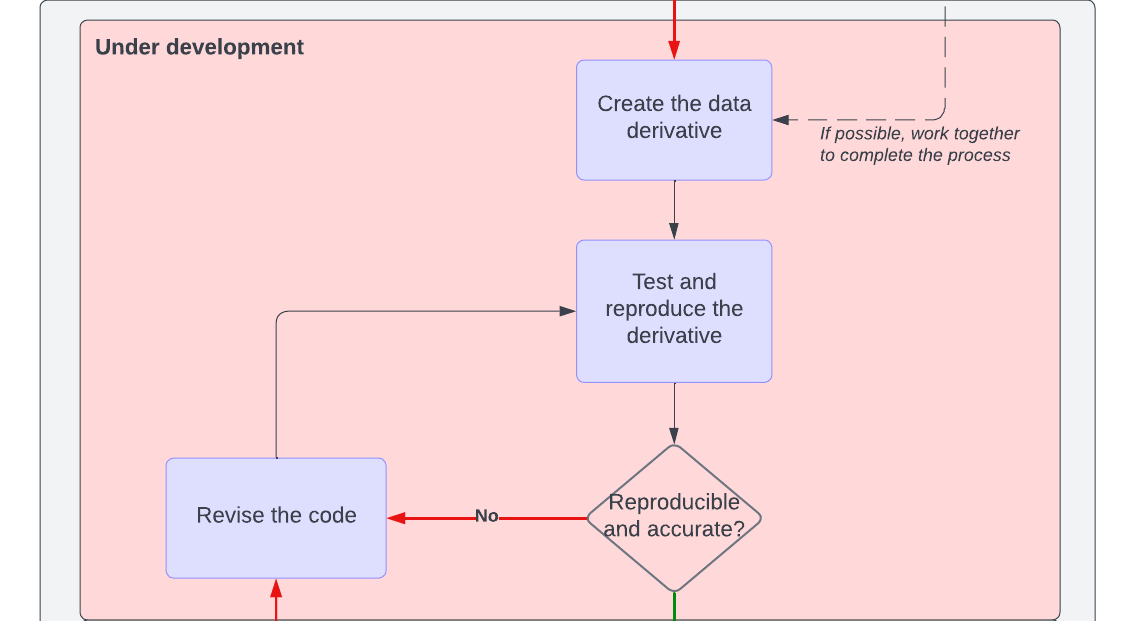

So you’ve come up with an idea for a derivative and you’ve checked the log–now what? It’s time to make the derivative!

Two key principles:

- Never modify raw/original data files. Always read raw data in to your environment and write to a new file. Be a good data steward, and save it somewhere safe that is accessible to others (as appropriate–ask your PI) and is regularly backed-up (i.e., not on your local drive).

- Never create a derivative manually (i.e., doing it “by hand”)–this limits reproducibility and increases the risk of human error. We get it–when trying to do something new, it may feel like you could accomplish it much faster by hand then by figuring out how to script it. But, we promise that the upfront cost to learn how to create a derivative via a script is worth it. First, you’ll learn a new and likely transferable skill. Second, you can be confident that the transformation/alteration is applied accurately to all of the observations. Third, you’ll create a script that you could apply to another, similar dataset later.

What if I want to develop several, related derivatives?

If you’re thinking of creating several, closely related derivatives, we think it makes sense to include the code to develop all of them in the same script. But they should be entered into the log as separate derivatives.

What if I don’t know how to get started?

If you’re not sure where to start, one option is to (1) write down what exactly you’re trying to create, (2) examine the raw data and/or the data dictionary, if there is one, and (3) determine what you need to do to go from the input data to the desired derived data. If you’re not sure how to script this, then check out the resources at the bottom of this page and/or ask someone in your lab with more coding experience for help!

Best and “good enough” practices

One could write multiple books about how to write readable, reproducible code (others have! see the list at the end of this page), so this is not meant to be a comprehensive guide. Instead, we have a few tips to get you started!

Variable naming

Thoughtful variable naming can prevent future headaches. Variable names should clearly describe what the thing you’re naming is. So single letter variables (e.g., x) or generic terms (e.g., fit) will likely be meaningless to you in a few weeks. They definitely won’t mean anything to your labmate or collaborator. You could also use variable names to convey multiple attributes, elegantly described by Emily Riederer.

Documentation

Code documentation should explain why, rather than what. If the reasoning behind a decision or a step isn’t obvious from the code itself, you probably should add a comment. Think about what information you’d need to understand the code if you closed the script and re-opened it a year later.

Other forms of documentation

Docstrings exist for a module, function, class, or method definition in Python

Code formatting

There are specific style guides and conventions for different languages.

- Python: PEP8

- R: the tidyverse style guide

- Matlab: Matlab style guidelines 2.0

There are some automatic formatters (e.g., blue and black for Python, formatR for R) that can help you quickly learn how to improve your code. At a minimum, we think it’s important to try to at least format your code consistently 1) within a script, 2) between your scripts, and 3) between scripts from your team members. Converging on consistent formatting is a great goal!

Derivative development checklist

For a code author before code review, see if you’ve completed these steps:

- Derived variables have been logged

- Purpose of the code is stated in the log

- The data inputs and outputs are stated in the log

- The code itself employs formats we have agreed to use (PEP8 for Python) (if none, is it internally consistent?)

- The folder, file, variable names, and outputs match formats we have agreed to use, if any (if none, are they internally consistent?)

- The code is modular, meaning that it derives a single variable or a small set of related variables; code for diverse variable types should be in separate scripts

- The use of hard-coded paths is minimized

- The code is sufficiently and efficiently commented

- After clearing and restarting my environment, I can reproduce the code on my own

- Provides output for comparison

- Raw data files are not overwritten or altered in any way

Resources

- a book about names: Naming Things

- a book about writing clean code: The Art of Readable Code

- a book about how to do data science in R: R for Data Science, 2nd edition

- a book about how to do data science in Python: Python Data Science Handbook, 3rd edition

If you know of a resource that would be a good addition to this list, please submit an issue and tell us about it!